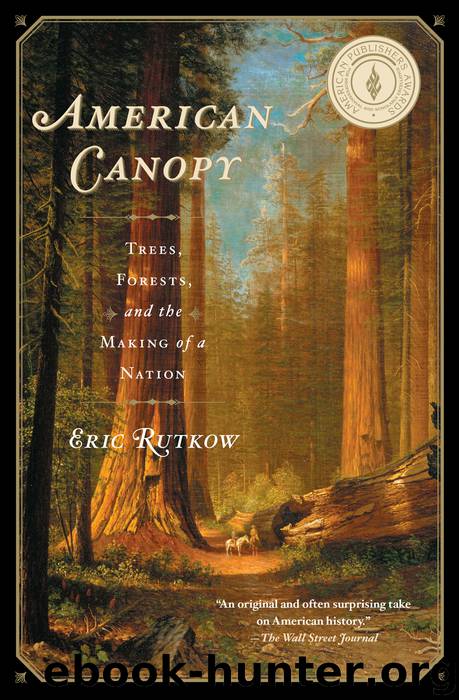

American Canopy by Eric Rutkow

Author:Eric Rutkow

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Scribner

“The Most Deadly Plant Parasite Known”

AMATURE AMERICAN CHESTNUT tree was a marvel of the forest, one that distinguished itself from other woody plants during all seasons. In the winter, when its branches were bare, it stood out on size alone, its columnar trunk soaring upward, its silhouette, often one hundred feet tall, shadowing nearly all other hardwoods. In the springtime appeared its distinctive leaves, long and canoe-shaped, punctuated with sharp points along the sides—botanists focused on this last feature when selecting a name for the species: Castanea dentata, the second part being derived from the Latin word for “tooth.” In the summer, usually in mid-July, long after most forest trees had flowered, the American chestnut finally set forth its blooms, a brilliant display that added a burst of color to the landscape—President Theodore Roosevelt, in his autobiography, fondly recalled that time each year “when the blossoming of the chestnut trees patche[d] the woodland with frothy greenish-yellow.” Of course, most Americans who thought about these trees thought about the fall months, when the species came into fruit. Each autumn, the branches grew heavy with an abundance of spiny green burrs, and inside of these, coddled in tan velvet, was one of the treasures of the forest, the American chestnut, whose sweetness and rich flavor were admired far and wide. Thoreau, in describing these nuts, once wrote, “They are plump and tender. I love to gather them, if only for the sense of the bountifulness of nature they give me.”

The American chestnut tree originally dominated much of the forestland in the eastern United States. Its natural range stretched north-south from central Maine to lower Alabama and east-west from the Atlantic seaboard to the far shore of the Mississippi River. Nearly everywhere within this massive territory, the tree appeared in substantial numbers—by some accounts it constituted 20 percent of all trees east of the Mississippi. Legend claimed that at one point a squirrel could bounce along the chestnut canopy from Georgia to New England without ever hitting the ground.

The finest region for chestnuts was the southern Appalachian Mountains, an area that included parts of North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. There, individual specimens could reach prodigious sizes, sometimes 120 feet tall and 12 feet in diameter. And in certain parts of the Appalachians, chestnuts grew in almost pure stands for miles on end. The nut production of these regions was remarkable—the chestnut mast could be more than a foot deep by late fall. Frederick Law Olmsted, who traveled through the southern Appalachians in the years before his appointment as superintendent of Central Park, observed, “[T]he chestnut mast is remarkably fine. The swine at large in the mountains, look much better than I saw them anywhere else at the South. It is said that they will fatten on the mast alone.”

Early American colonists needed little time to recognize the importance of chestnut trees to daily life. The nuts, a favored food source for many Native American tribes, offered easy sustenance in a foreign environment.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4801)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4467)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4314)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3956)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3824)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3691)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3622)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3466)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3356)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3338)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3316)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3297)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3220)

Origin Story by David Christian(3198)

Water by Ian Miller(3181)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3071)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2930)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2860)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2839)